In the early 20th century, the radio burst onto the scene, captivating America in a way no one had anticipated. Suddenly, the nation could experience events in real time. Gone were the days of waiting for hours or even days to hear the latest news from Washington if you lived on the West Coast. Radio brought people together, uniting the country like never before.

Enter David Sarnoff, the ambitious general manager of RCA, the leading radio broadcast company in America. Sarnoff saw immense potential in the radio industry and aimed to dominate it. RCA wasn’t just manufacturing radios; they owned over 2,000 radio patents. Sarnoff believed big money lay in those patents. By licensing them, RCA turned competitors into customers every time a radio sold. It was an empire-building strategy that worked spectacularly well.

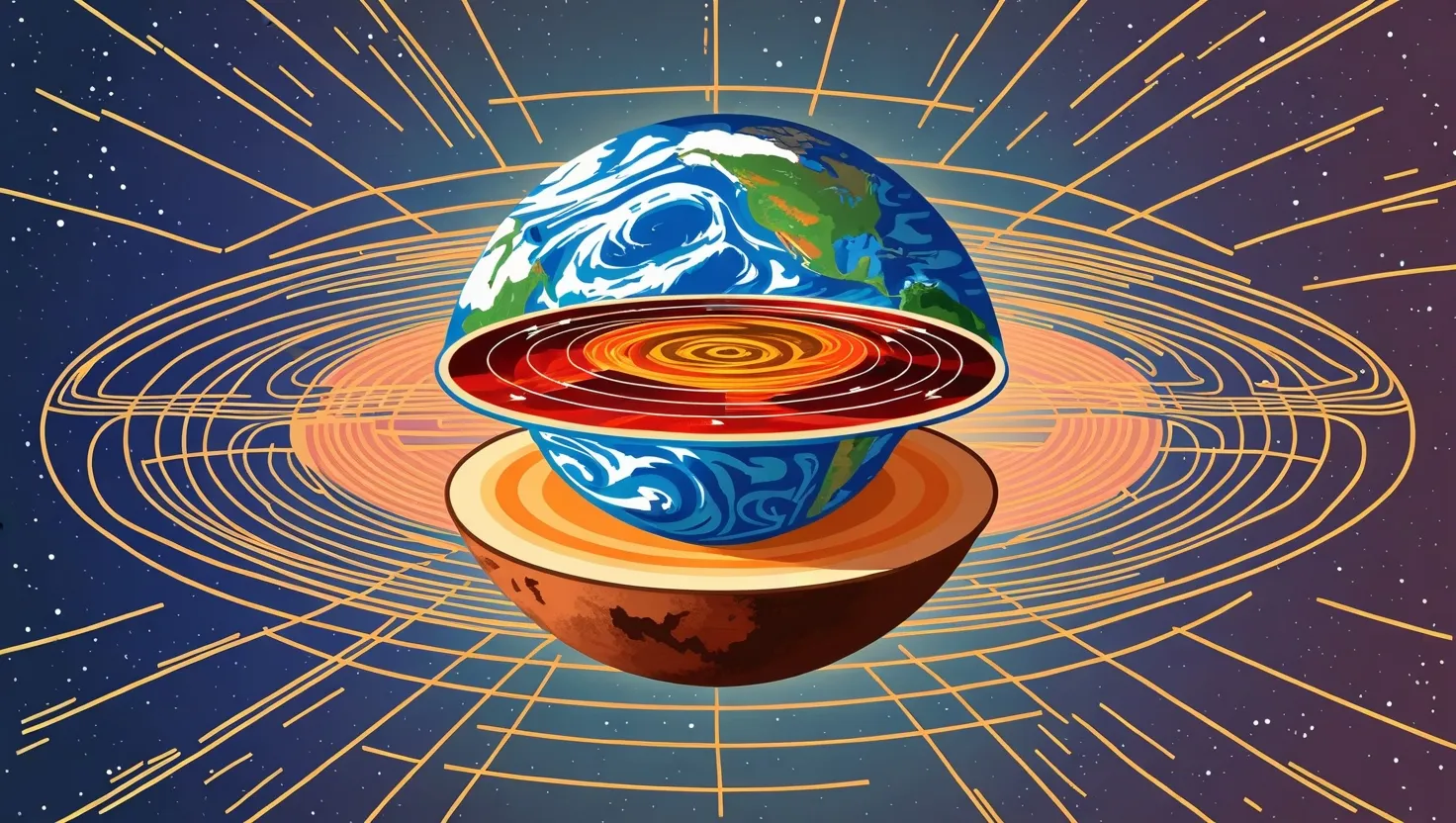

As radio’s popularity soared, RCA’s profits did too. But even as Sarnoff built his media empire, a young farm boy miles away dreamt of something that could make radio obsolete—Philo Farnsworth envisioned television. Despite his roots on a potato farm, Farnsworth was a prodigy with a knack for electronics. Inspired by the lines in his father’s plowed field, he figured he could scan images electronically, much like how a microphone captures sound.

His natural talent and relentless drive led him to develop the first concept of an electronic television by the age of fifteen. However, realizing that dream would take years of effort, personal sacrifices, and financial struggles. After moving to California with his wife, Farnsworth set up a lab to turn his idea into a reality. A fortunate investment allowed him to create a prototype, but initial tests failed.

David Sarnoff, determined to secure RCA’s future, saw the threat television posed to his radio empire. While Farnsworth continued refining his design, Sarnoff poured vast resources into developing his own version of the technology, recruiting the brilliant Vladimir Zworykin. Despite legal battles and financial roadblocks, Farnsworth succeeded in getting his television patent approved in 1930, cementing his status as the inventor of electronic television.

Sarnoff, however, wasn’t one to be easily defeated. Using his clout, he delayed Farnsworth’s progress and pressured competitors like Philco into abandoning their support for Farnsworth’s TV. Ultimately, legal battles drained Farnsworth’s resources and energy, driving him to the brink.

In a twist of fate, RCA had to license Farnsworth’s patents to make their television work. Even though the courts and the patent office recognized Farnsworth’s invention, Sarnoff’s relentless maneuvers and the onset of World War II delayed television’s widespread adoption.

By the time the war ended and television finally took off, Farnsworth’s patents had expired. RCA, led by Sarnoff, capitalized on the TV boom, selling thousands of sets and launching the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). Television quickly became a household staple, and RCA’s profits soared.

Philo Farnsworth experienced a bittersweet redemption years later, watching the Apollo moon landing—the very vision he had for television, bringing people together through a shared, powerful moment. Although David Sarnoff introduced television to the masses, history eventually acknowledged Philo Farnsworth as the true inventor of one of the most transformative technologies of the 20th century.