In the intricate web of life on Earth, certain creatures challenge our understanding of survival and resilience. Standing out among these is the tardigrade, a diminutive wonder of nature that has fascinated scientists and enthusiasts alike. Also known affectionately as the “water bear” or “moss piglet,” these microscopic invertebrates measure just 0.1 to 1.5 millimeters in length. Yet, their size doesn’t stop them from being one of the most robust life forms, surviving conditions that would obliterate most other creatures.

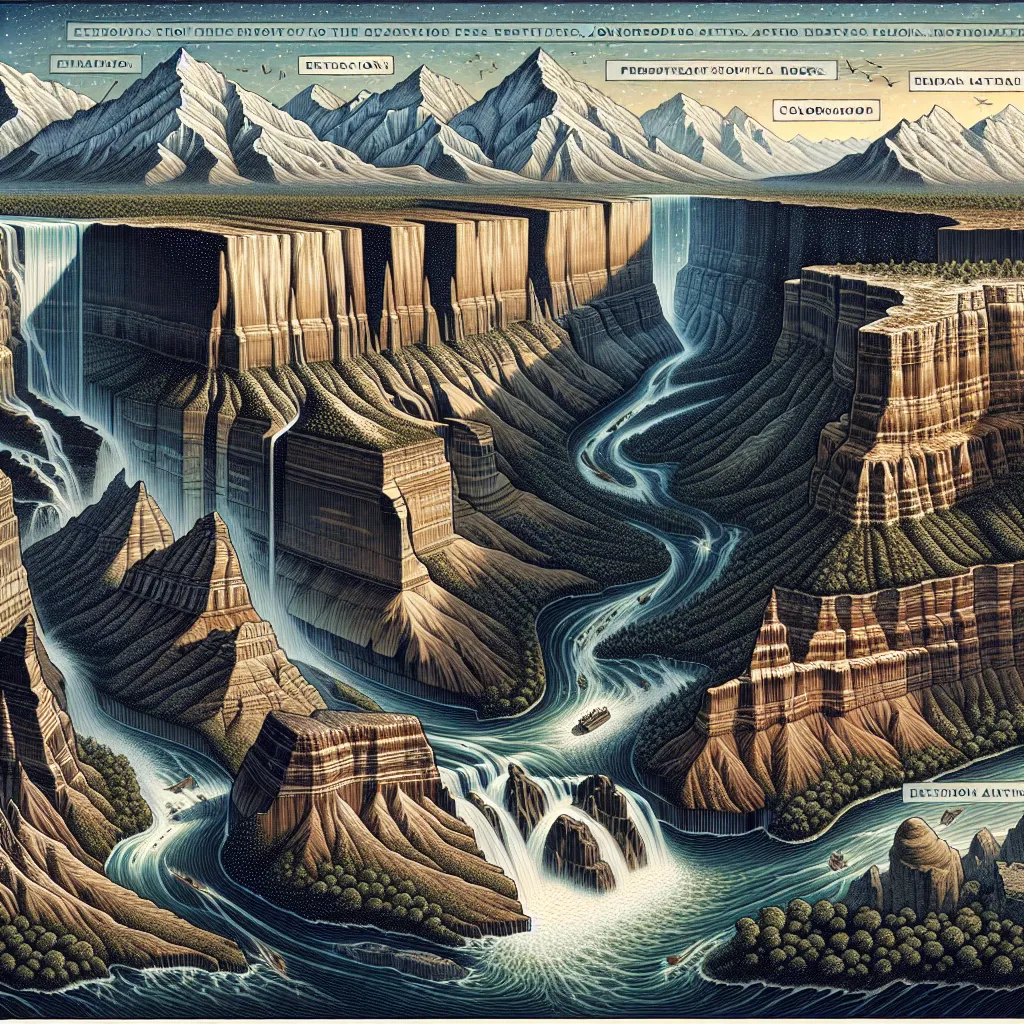

Tardigrades are, without a doubt, the ultimate survivors. They can be found in a wide variety of environments—terrestrial and aquatic—ranging from the depths of the ocean to the lofty peaks of mountains, even stretching to the icy realms of the polar regions. There are over 1,300 identified species of tardigrades, showcasing an incredible diversity that sees them thriving in habitats all over the globe. From the scorching deserts to the frigid lengths of Antarctica, these tiny creatures show up where most life forms wouldn’t dare to exist.

Physically, tardigrades sport a set of unique features that make them stand out. Their bodies are segmented, and they move around using four pairs of stubby legs equipped with claw-like structures. These adaptations allow them to cling to surfaces and navigate with surprising agility. Covered in a protective yet flexible cuticle, these features combine seamlessly to help tardigrades inhabit and endure in a myriad of environments.

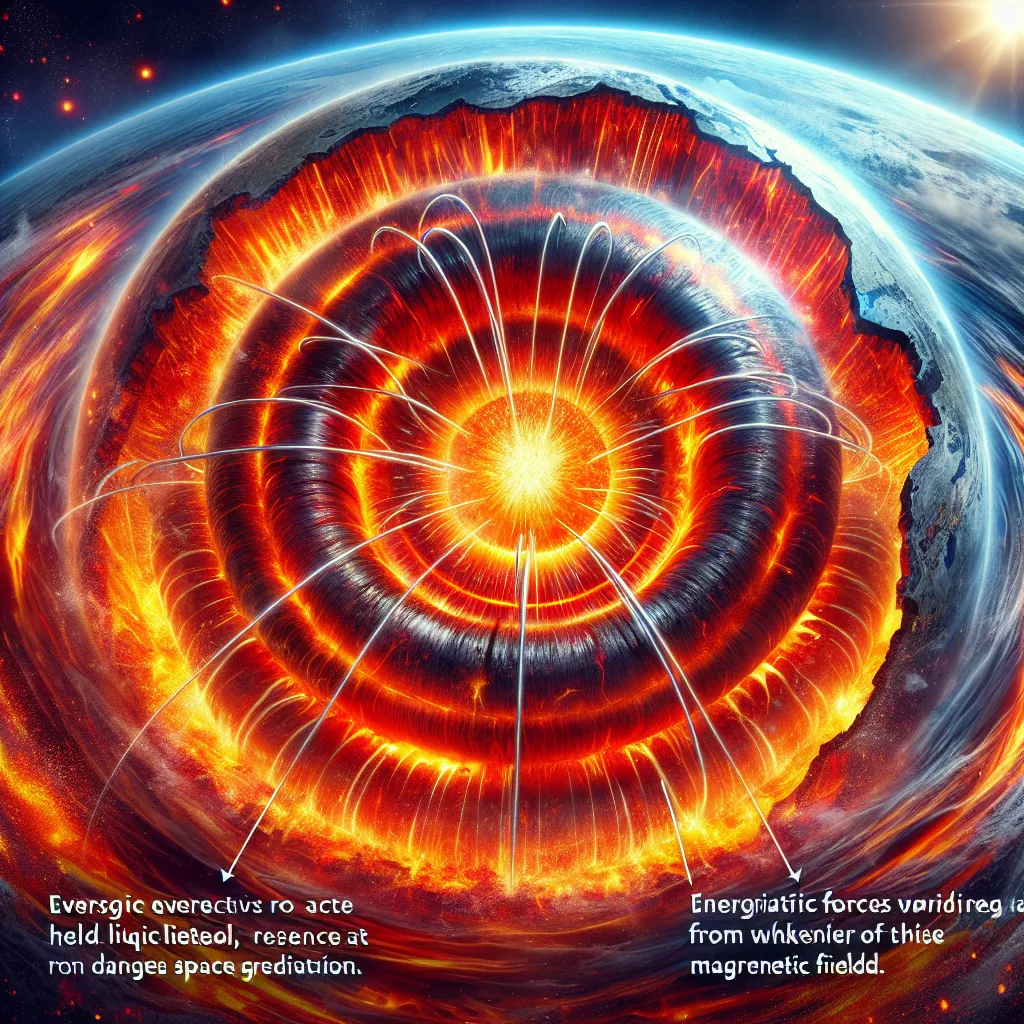

But what truly sets tardigrades apart is their incredible survival mechanisms. Their claim to fame is cryptobiosis, a state likened to suspended animation, allowing them to weather harsh conditions like extreme desiccation, freezing, and intense radiation. Essentially, their metabolism shuts down, and almost all water content in their bodies vanishes, enabling them to survive for years, even decades, until they find more hospitable conditions. Tardigrades have been known to withstand temperature extremes, from a bone-chilling -273°C (-459°F) to a blistering 150°C (302°F). They thrive under conditions that would cause most life forms to perish immediately, such as the intense heat of deserts or the freezing climates of polar regions.

Their resilience doesn’t stop at temperature extremes; tardigrades also exhibit remarkable resistance to radiation. They expose themselves to levels of ionizing radiation hundreds of times higher than what would be fatal to humans. Scientists have discovered that these creatures can ramp up the production of DNA repair genes, which permits them to remedy extensive DNA damage inflicted by radiation—an extraordinary trait that’s pivotal to their survival.

Tardigrades are equally impressive when it comes to pressure tolerance and chemical resistance. These creatures have been found deep within ocean trenches, surviving in pressures thousands of times greater than those at the surface. Additionally, they have a knack for enduring harsh chemicals, such as strong acids, alkaline solutions, and various organic solvents.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of tardigrade resilience is their ability to survive the harsh environment of outer space. They’ve been part of space missions, enduring the vacuum and radiation beyond our atmosphere. Astonishingly, they’ve managed not only to survive but also to reproduce under these conditions—a testament to their potential for surviving interplanetary voyages.

The genetic foundation of this resilience has intrigued researchers for a while. Recent studies employing the CRISPR technique have enabled scientists to edit tardigrade genes, unveiling the specific genes responsible for their resilience. Tardigrades boast unique gene families contributing to their extremotolerance. For instance, they possess certain proteins that guard their DNA against radiation and help them weather desiccation.

Delving deeper into their survival tactics, anhydrobiosis stands out as particularly intriguing. In this state, tardigrades virtually rid themselves of water, with their body water content plunging to a mere few percent. Their metabolic activities pause, letting them withstand temperatures up to 100°C while being resistant to radiation and high pressure. Upon rehydration, their biological functions can restart within minutes.

These survival strategies are likely honed over hundreds of millions of years. Tardigrades have roamed the Earth for about 600 million years, making them significantly older than the dinosaurs, by around 400 million years. Their ability to survive some of Earth’s most tumultuous extinction events cements their reputation as ancient survivors. Their impressive adaptivity offers glimpses into their evolutionary journey, suggesting independent transitions from marine to limno-terrestrial environments led to such extraordinary survival capacities.

Understanding tardigrades not only elevates our appreciation for Earth’s biodiversity but also aids in the quest for life beyond our planet. Their tenacity serves as a testament to life’s enduring power and diversity. Decoding tardigrade resilience could spark innovations to protect other organisms from severe radiation and extreme conditions.

As research continues, the implications for human benefit are growing. Discovering gel proteins in tardigrade cells that aid their survival during severe dehydration has raised the possibility of applying similar techniques to human cells—a breakthrough that could revolutionize organ donation, transportation, and surgical applications, potentially saving countless lives.

Tardigrades remind us that life is far more adaptable and resilient than we ever imagined. Their remarkable survival skills challenge our understanding of life’s boundaries and light up pathways for research in fields stretching from biology to astrobiology. Diving into the mysteries of these mighty microscopic creatures affirms the tenacity and extraordinary capacity of life to endure, inspiring awe and scientific inquiry alike.