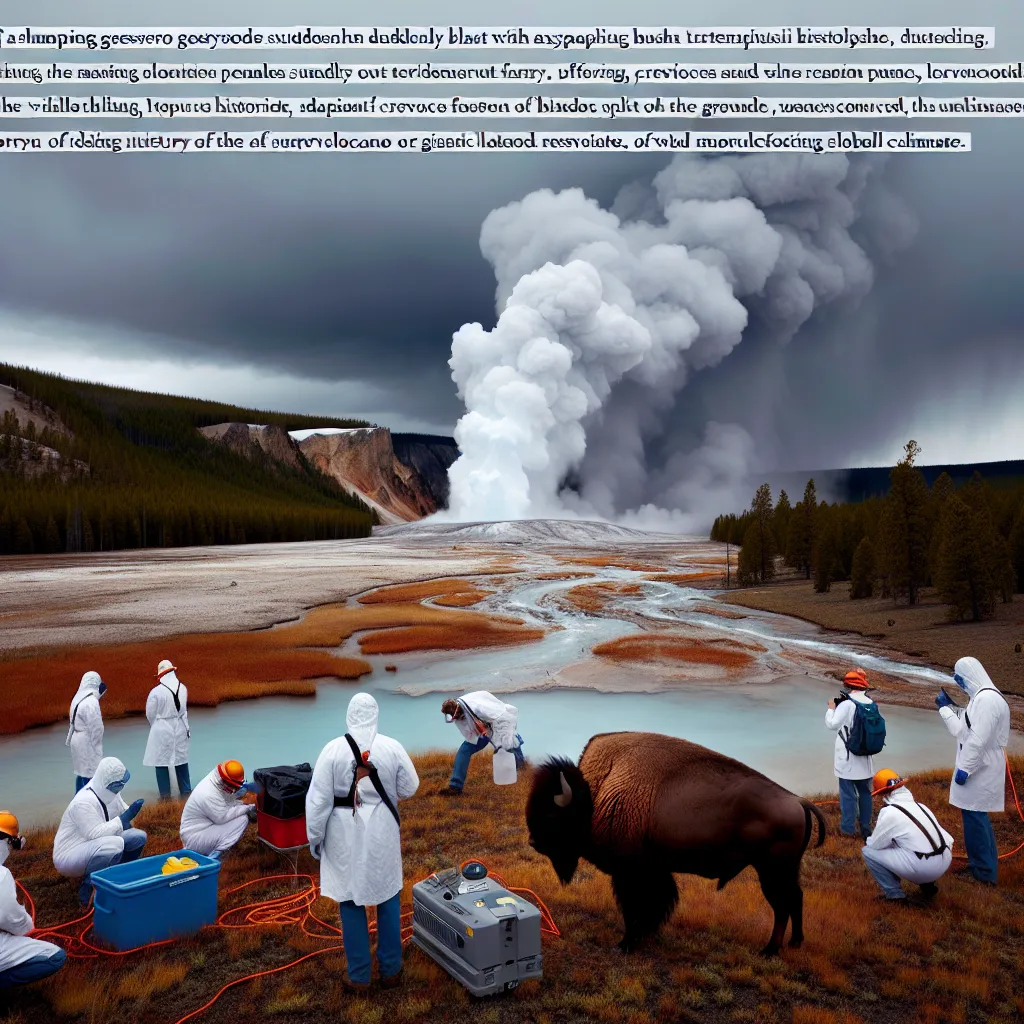

Yellowstone, Wyoming, Spring of 2003. Something strange was brewing in America’s most famous national park. Usually, the tallest geyser in the world goes 50 years without erupting. But suddenly, it sprang into life, shooting columns of superheated water hundreds of feet into the air. New cracks formed in the ground, and the ground heated up to the point where the National Park Service had to close some trails. Then, a group of bison collapsed and died, victims of poisonous fumes leaking from the earth. Satellite images showed ominous signs beneath Yellowstone, sparking unfounded internet rumors that a super volcano was about to blow.

Imagine the biggest explosion you can think of, and then scale it up a million times. That’s what a supervolcano eruption looks like. Regular volcanoes are no match for this beast. They might shoot ash over an entire state, but a supervolcano? It could blanket half of the United States. Over the history of the Earth, more than 20 supervolcano eruptions have been recorded, with over half in North America. If Yellowstone erupted today, the United States might not stand a chance.

Yellowstone National Park is a serene wilderness with hot springs and geysers attracting tourists for over a century. Few realize the hidden terror beneath its picturesque landscape. Geologist Bob Christensen spent years studying Yellowstone’s rocks, uncovering its dangerous past. It turns out Yellowstone is home to one of the planet’s active supervolcanoes. This threat became painfully clear in 1959 when a major earthquake triggered a landslide that killed 28 campers at Hebgen Lake. Since then, Yellowstone has become a laboratory for monitoring its volatile nature. Geologists discovered that Yellowstone averaged over 25 earthquakes a week.

In search of the source of these eruptions, Christensen realized the park had been the site of enormous eruptions in the past. Instead of finding a classic cone-shaped volcano, he found a colossal crater, known as a caldera. This was the smoking gun he sought. When a caldera forms, it’s because a massive magma chamber beneath the surface has collapsed. In Yellowstone’s case, the chamber was a staggering 50 miles long and 25 miles across.

The Yellowstone caldera has seen three major eruptions, each depositing hundreds of cubic miles of ash — enough to bury Texas under five feet. These eruptions were 1,000 times the size of the Mount St. Helens blast. One can only imagine ash flying miles into the sky, spreading and blanketing the land for hundreds of miles.

An eruption like Yellowstone’s would produce ash clouds capable of reaching the stratosphere, affecting global climate. This has happened before. The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 led to the “Year Without a Summer,” causing widespread crop failures and famines. A Yellowstone eruption would be many times worse, potentially altering the climate for years and endangering millions of lives.

In 2003, a series of unusual seismic activities at Yellowstone raised red flags. Geologists noticed the ground rising, likely due to the magma chamber below. Though these signs indicate activity, modern technology like seismometers keeps constant watch over the park. Scientists are trying to predict when, not if, the next big eruption will occur.

The current monitoring suggests that Yellowstone’s magma chamber has only about 10% melt, indicating it’s not ready for a super eruption anytime soon. But could we ever prevent such a disaster? Drilling thousands of holes to release pressure isn’t viable; it’s technologically impossible to manage a system this vast and would have negligible effects.

If Yellowstone erupts, it could cripple the United States. Thousands might die instantly, followed by millions more suffocating on ash or succumbing to famine. However, detailed disaster planning could offer some hope for survival. Scientists are tasked with vigilantly monitoring Yellowstone, ensuring we aren’t blindsided by another supervolcano eruption.

Supervolcanoes are rare, occurring roughly every 700,000 years. But Yellowstone sits at the heart of America, patiently waiting. Our only hope is to stay vigilant, prepare adequately, and continue advancing our technology to predict and manage such a catastrophic event.