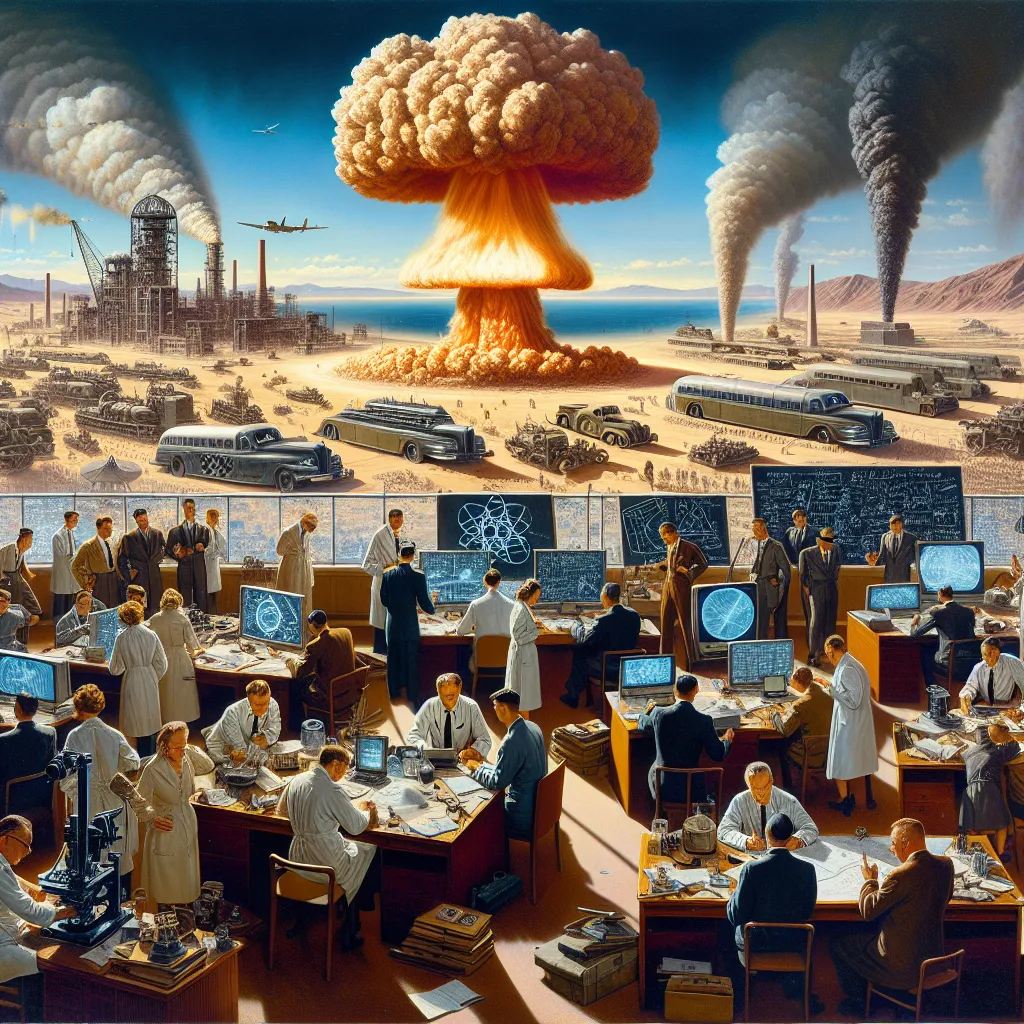

In 2000, NASA launched an ambitious mission to explore Mars, sending two rovers to the red planet’s surface for a three-month adventure. Leading this project, Professor Steve Squyres dedicated 16 years to making it happen. He had no idea how rough the road would actually be. A lot was riding on this mission as two previous Mars probes had ended in failure due to mix-ups and technical glitches.

Squyres’ mission was born out of these earlier setbacks, taking on the challenge to build and launch two new rovers within an inflexible three-year deadline. The technical challenges were immense. The rovers had to endure a bone-shaking launch, a seven-month flight, and then hit a re-entry window just four miles wide at speeds of 12,000 miles per hour. Once they reached Mars’ atmosphere, a complex parachute system would slow them down to just 12 miles per hour, allowing them to bounce to a standstill with the help of airbags. Only then could their real mission begin.

The engineers had one significant advantage: the success of the Pathfinder mission three years earlier. Although Pathfinder hadn’t traveled far, it proved that roving on another planet was possible. The new rovers, however, were more advanced and packed with sophisticated instruments. But a critical problem arose – the rovers ended up being too big to fit in the lander.

The team scrambled to build a bigger craft to carry the rovers to Mars. After two intense years of design and assembly, they finally got the chance to see the fully assembled rovers in action. It was an emotional moment for everyone involved, a testament to the immense effort and dedication poured into the project.

At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Labs in California, a simulation of Martian terrain awaited the rovers. They needed to travel miles over harsh, dusty terrain in frigid temperatures. Key to their survival was an innovative wheel design that combined shock-absorbing capabilities with flexible joints, allowing the rovers to navigate rocky obstacles.

With the final design set and just seven months left, the team focused on the parachutes. These had to work perfectly in Mars’ thin atmosphere at supersonic speeds. Lead engineer Adam Steltzner spearheaded this critical phase. The parachutes, designed as a disc-gap band system, needed rigorous testing. The first full-scale test, tragically, ended in failure – the parachute shredded apart.

Undeterred, the team went back to the drawing board, creating three new designs. Testing continued in the world’s largest wind tunnel, where another failure revealed a “squidding” issue caused by an oversized vent hole. After correcting this, a successful test brought much-needed relief.

By May 2003, the rovers and spacecraft were nearly ready for launch. But a new problem emerged just weeks before the deadline – faulty pyrotechnic charges meant to release critical bolts and cables. With the rocket already on the pad, the team raced against time to fix the issue. The success of their mission hinged on overcoming this final hurdle.

Through relentless determination and innovation, NASA’s team managed to keep the mission on track. Their efforts would ultimately pave the way for a groundbreaking exploration of the red planet.