In 1939, Albert Einstein sent a pivotal letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, urging the exploration of nuclear chain reactions as World War II raged on. Roosevelt responded by creating the U.S. uranium project, later known as the Manhattan Project, under military control in 1942. This led to the first controlled nuclear reaction beneath a football stadium in Chicago.

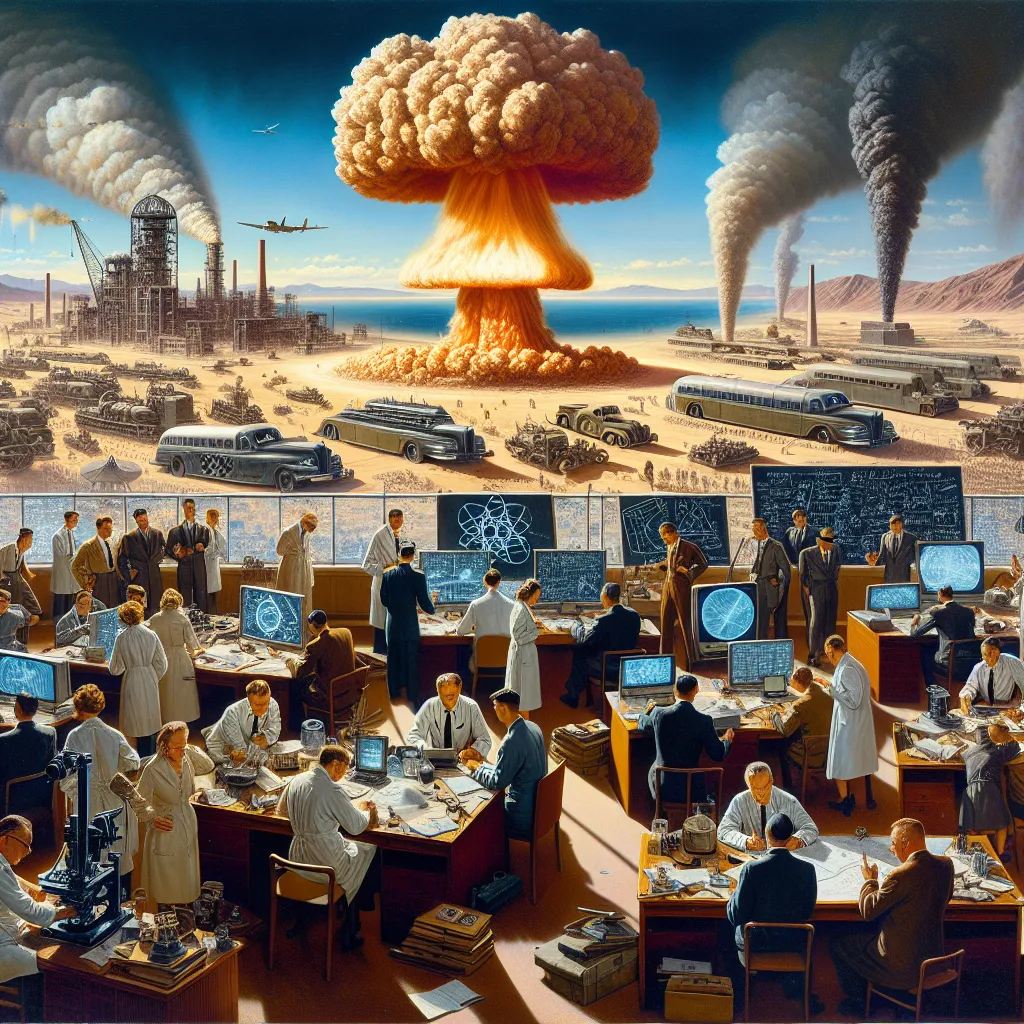

The Manhattan Project soon became the world’s largest weapons development initiative, involving hundreds of thousands of workers across 17 sites in 12 states. Key sites included Los Alamos, where Robert Oppenheimer’s team focused on the bomb’s physics, and massive industrial plants in Tennessee and Washington to produce plutonium. All operations were shrouded in extreme secrecy.

After years of intense research and billions of dollars, the Manhattan Project yielded its first success on July 16, 1945. An atomic bomb with a force of 22 kilotons exploded in the New Mexico desert, far surpassing any previous explosives. The scientists behind this project understood the immense destructive power they had unleashed and grappled with the morality of their creation. Many of them were Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, which influenced their belief in the project’s necessity.

Although initially aimed at Germany, the bomb was ultimately used against Japan. On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped a bomb dubbed “Little Boy” over Hiroshima. The explosion caused immediate devastation, wiping out 80,000 lives and injuring another 80,000. The flat terrain of Hiroshima amplified the bomb’s devastating impact, turning 13 square kilometers into ruins.

Despite the horrifying destruction in Hiroshima, Japan did not immediately surrender. Just three days later, on August 9, a second bomb, “Fat Man,” was dropped on Nagasaki. Though Nagasaki’s hilly terrain slightly mitigated the bomb’s effect, it still killed 40,000 people.

The dual atomic bombings and Russia’s invasion of Manchuria pressured Emperor Hirohito to surrender, ending World War II. However, the use of atomic bombs also signaled to the world, particularly Russia, that the U.S. possessed a formidable new weapon, thus igniting the Cold War.

By 1950, the world had hundreds of nuclear weapons. This arsenal grew exponentially, marking the beginning of an arms race. The Cold War was characterized by a delicate balance of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD), which discouraged direct conflict between nuclear powers.

In 1952, the U.S. tested “Mike,” the first hydrogen bomb, on the Enewetak Atoll, producing an explosion 500 times more powerful than the Nagasaki bomb. This ushered in an era of even more powerful nuclear weapons, transforming warfare and geopolitics.

Over the next few decades, the number of nuclear weapons skyrocketed, peaking at over 61,000 during the Cold War. Today, around 16,000 nuclear weapons remain, a sobering reminder of their potential for unparalleled destruction. The sheer power of these weapons has kept great powers from waging wars against each other, maintaining an uneasy peace through the principle of nuclear deterrence.