The devastation that swept across the Indian Ocean was like something out of a horror movie. It was the kind of disaster that leaves you speechless—a massive wave that stopped at nothing, flattening everything in its path and snuffing out more than a quarter of a million lives. It was the most unimaginable natural disaster in the last century, turning the word “tsunami” into a universal term of dread.

Imagine a cataclysmic train wreck where the front grinds to a halt and the rear crashes into it, obliterating everything. That’s what a tsunami does. It’s not just a wave; it’s an unstoppable force of nature. But beyond fear, there’s a pressing question: Are we ready for the next one? Big cities lie in jeopardy, and we’re left wondering who will next face this awful gamble.

Understanding tsunamis—their creation, speed across oceans, and sheer destructive nature—can help us brace ourselves for future threats. On that awful day after Christmas in 2004, most people in Sumatra and Indonesia had no warning. Meanwhile, scientists at the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, hundreds of miles away, watched frantic seismic readings, feeling powerless because their tools served only the Pacific Ocean, not the Indian Ocean.

Under the command of Barry Hirschhorn and Stuart Weinstein, alarms blared and computers came to life, but there was no way to send warnings to the Indian Ocean shores. The instruments designed to save lives couldn’t reach the coastlines that needed them most. As they struggled with a lack of sensors in the Indian Ocean, the waves were already wreaking havoc, unseen and deadly.

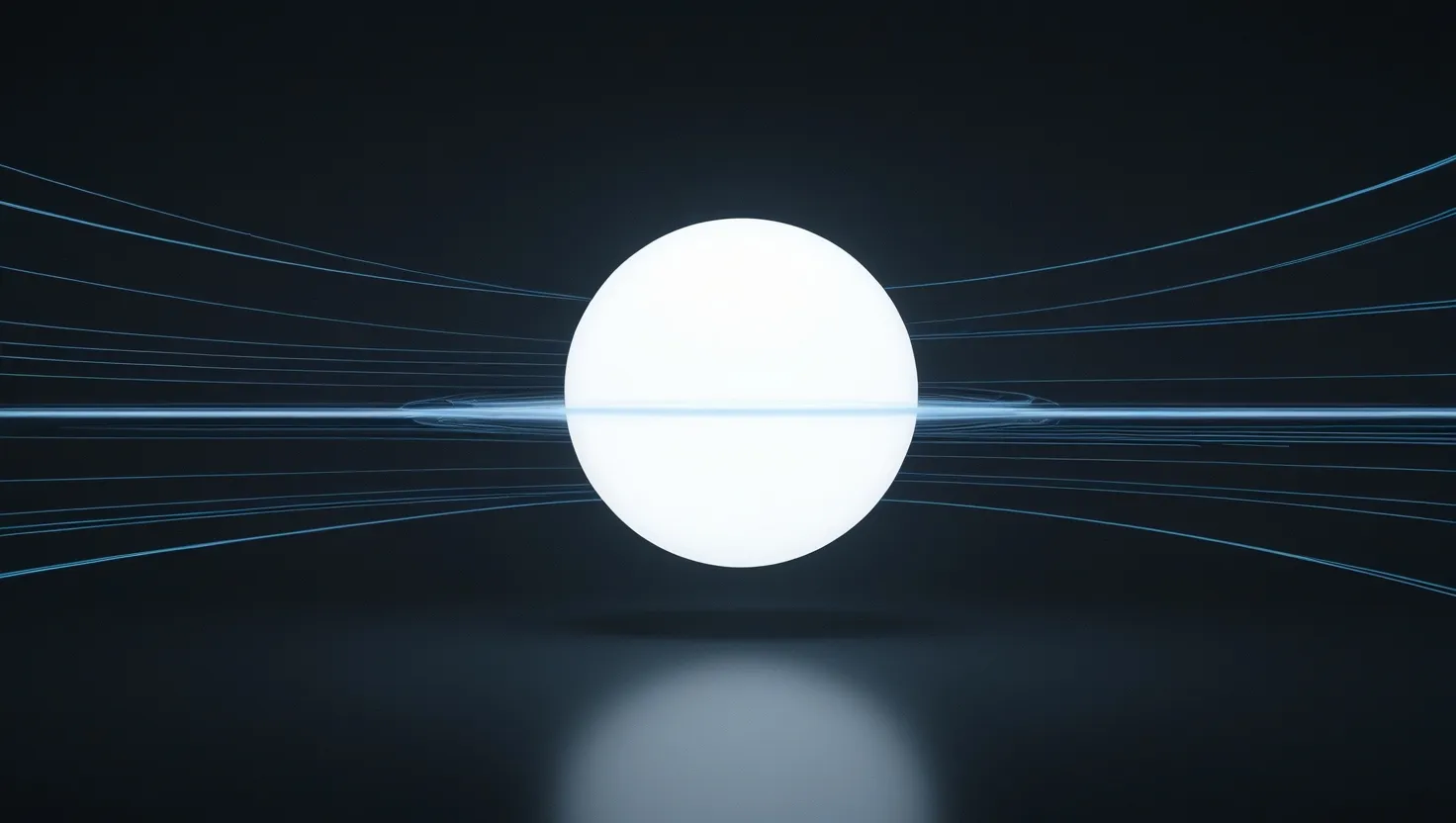

Normal waves might intimidate surfers, but they’re tame compared to a tsunami. Tsunami waves act differently—they’re born from undersea activities like earthquakes, volcanoes, landslides, or even asteroids, each capable of pushing massive amounts of water. When these waves hit, it’s like the entire ocean is rising to engulf the land. This differs from normal waves that break and retreat quickly; tsunami waves roll in like a relentless, lethal river, pushed by the immense energy lurched into motion on the seafloor.

The 2004 tsunami was triggered by one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded, causing a massive section of the ocean floor to jolt upwards by about 10 feet. This uplift transferred immense amounts of energy to the water above—a critical detail scientists like Walter Dudley use to understand and predict future tsunamis’ behavior.

As terrifying as they are, tsunamis aren’t limited to tectonic shifts. In 1883, Krakatoa’s volcanic eruption was so explosive it created 130-foot waves, killing tens of thousands. Tsunamis can also be caused by underwater landslides, like in 1998 near Papua New Guinea, where the slipped seabed sparked a deadly wave.

Asteroids too, can stir up catastrophic tsunamis if they slam into our oceans. An asteroid of just a few miles in diameter crashing into the sea could send deadly waves across entire continents.

As scientists race to predict these waves, they scrutinize earthquake history in tsunami-prone areas. These insights come not from high-tech gadgets alone but sometimes simple natural records like coral reefs—living seismographs showing how often significant uplifts occur.

While we work on more advanced warning systems like the DART project, pressure sensors at the ocean’s floor designed to recognize approaching tsunamis, there’s still a daunting hole in protection. Earthquakes near the shorelines need immediate human reaction rather than waiting for tech alerts. Coastal areas must have clear evacuation routes and constant public education on tsunamis’ telltale signs.

Sometimes, community knowledge alone saves lives. In December 2004, the islanders of Simalu, having passed down stories of past tsunamis, knew to run for higher ground when the earth shook, saving nearly everyone. It’s a strong reminder that while technology can assist, local wisdom and preparation are crucial.

Moving forward, the planet needs sophisticated alert systems paired with robust education campaigns. People must know when and how to evacuate, relying on both state-of-the-art systems and ancient wisdom. The science of tsunamis is evolving, but until we grasp it fully, the best defense is knowledge and readiness.