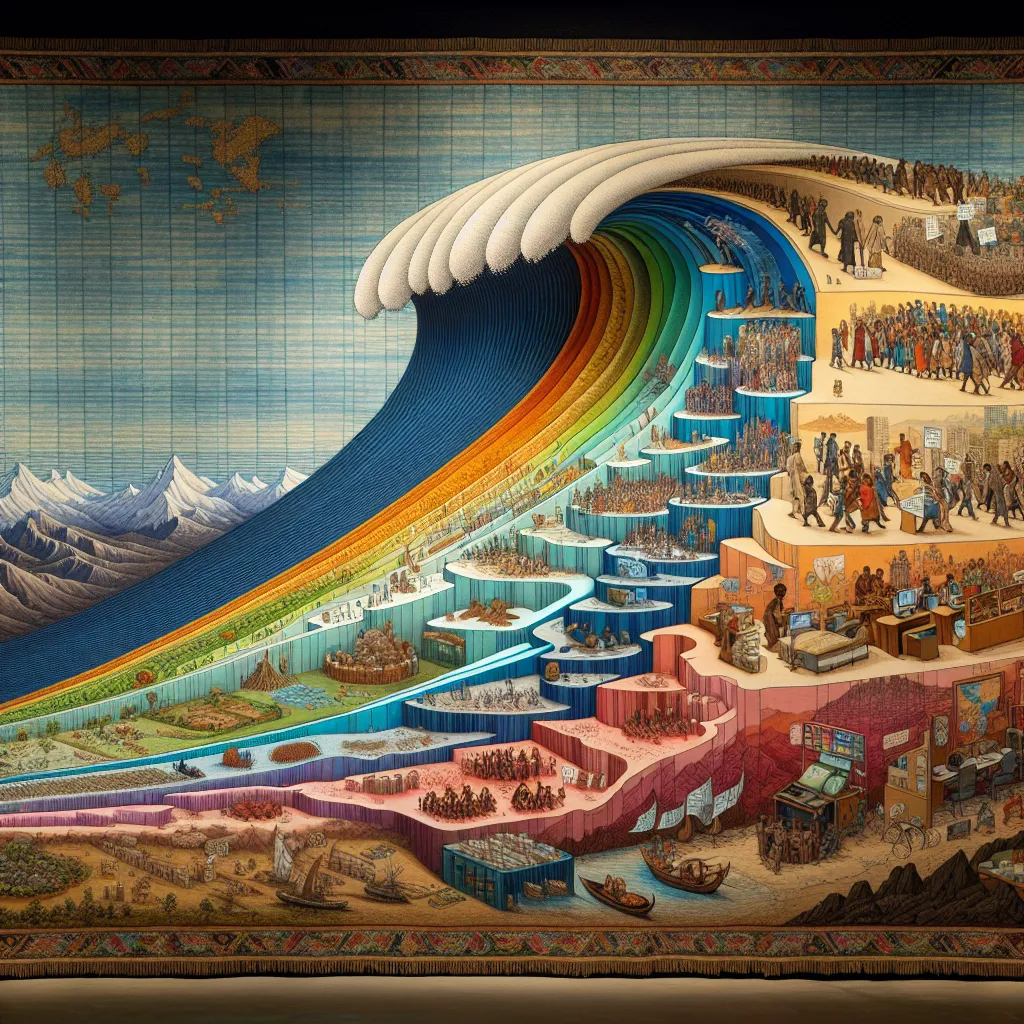

Human history shows that our population grew slowly for most of the time. Then, new discoveries upped our food production and improved our lifespan. Fast forward a century, and our population quadrupled, sparking fears of overpopulation. However, population growth peaked in the 1960s. Since then, many countries have seen crash fertility rates as they industrialized and developed. We’re now expecting the global population to balance out at roughly 11 billion by the century’s end.

For a closer look, consider Sub-Saharan Africa. Back in 2019, it housed a billion people across 46 nations. Despite slowing growth rates, it still grows faster than the rest of the world. Projections estimate a population between 2.6 and 5 billion by 2100—a daunting figure for a region that’s also the poorest on Earth. But these projections vary widely due to multiple factors.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a term that blankets a diverse set of countries with vastly different circumstances. For example, Botswana and Sierra Leone are as different as Ireland and Kazakhstan. When talking to scientists, there was no unanimous view on how much fertility rates impact poverty. But let’s look at the global context.

A few decades ago, countries like Bangladesh were in a similar situation as some African nations now. In the 1960s, Bangladeshi women had an average of seven children, with high child mortality rates. Bangladesh turned things around with education, better healthcare, and family planning. These measures drastically slowed down population growth. By 2019, the average number of children per woman dropped to two.

Why hasn’t Sub-Saharan Africa seen similar progress? Although strides in child mortality have been made, education and access to contraception haven’t kept pace. Many nations only recently gained independence, faced civil unrest, or endured unstable governments, hindering infrastructure and healthcare expansion. The effects of foreign aid during the Cold War are also complex, adding another layer to the issue. Plus, cultural factors make family planning a sensitive topic.

Despite these challenges, potential solutions exist. Investments in education, healthcare, and family planning could make a huge difference. Even small changes, like delaying the age of first childbirth by two years, could result in 400 million fewer people by 2100. Universal access to contraception could significantly reduce birth projections.

There’s already a success story in Ethiopia. The country has implemented health services and invested in education, dropping child mortality and increasing school numbers. These examples show that while challenges are significant, they are not insurmountable. Sub-Saharan Africa has immense potential, and with the right attention and fair investment, a turnaround like Asia’s in recent decades is possible.