Consciousness is one of nature’s biggest mysteries. At its core, it’s what lets us be aware of our surroundings and our inner state. It’s something we all experience, yet defining it feels like chasing smoke. Even philosophers and scientists can’t fully explain consciousness. Various theories exist, but no one has nailed it yet. It’s a bit unsettling to realize that we have yet to understand what makes us aware of ourselves and the world.

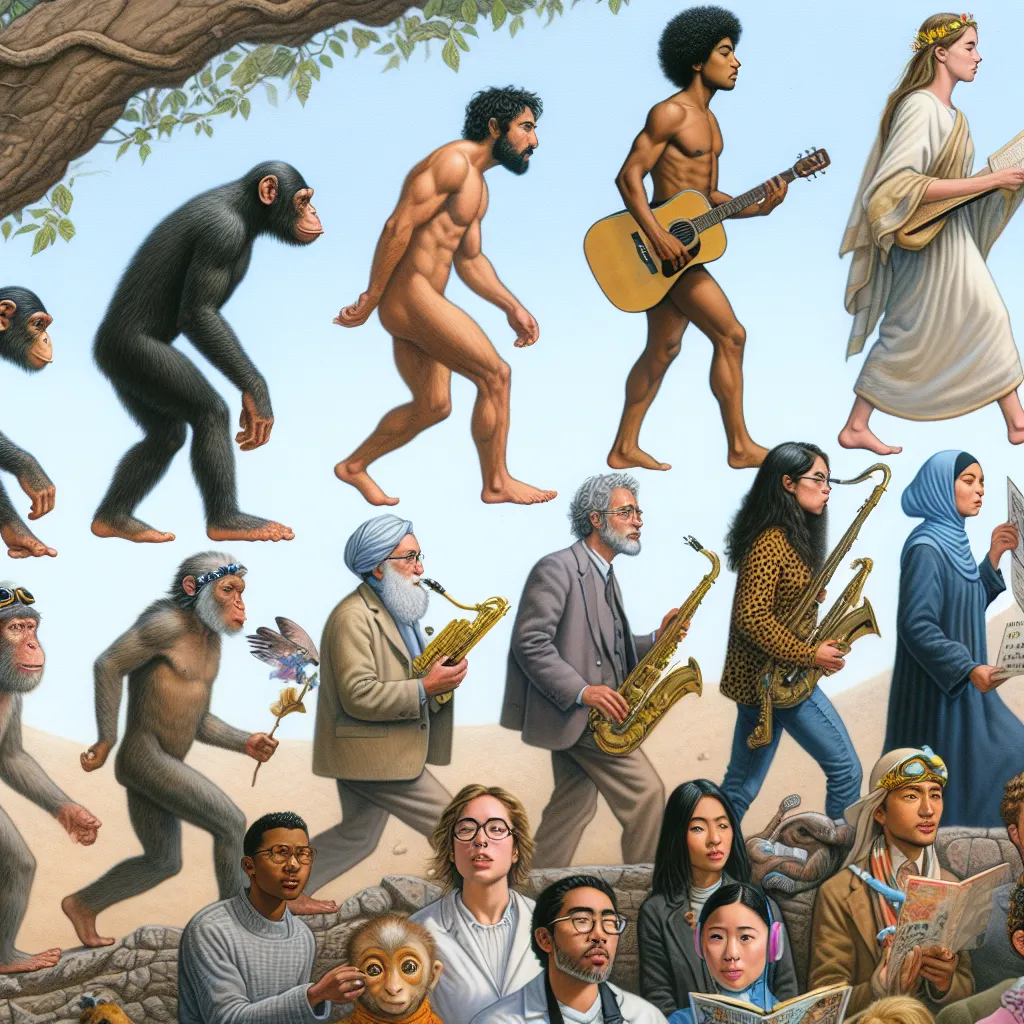

Consciousness seems related to intelligence, but they’re not the same. We’ll dive deeper into these topics in other pieces. Like many aspects of being human, our consciousness likely evolved over millions of years. This evolution involved countless small steps, eventually leading to the complex consciousness we enjoy today.

Starting with inanimate objects like stones, which we generally consider non-conscious, we see no behavior suggesting they have inner lives. However, some panpsychists argue that even a rock might have some form of consciousness. But since rocks don’t show any behavior, there’s no way to prove or disprove this idea.

Living beings are a more common starting point for discussing consciousness. A living entity, or a “self,” is a part of the universe that sustains itself and reproduces. For this, it needs energy, and being aware of its environment becomes useful. The initial purpose of consciousness was likely to help a mobile self find food.

On a smaller scale, some creatures don’t need to be aware to find food. Take Trichoplax adhaerens, a simple animal that moves randomly. It slows down around food and speeds up when there’s none, effectively spending more time where food is present. But it doesn’t move towards any specific target, indicating no need for consciousness as we understand it.

The first big leap toward consciousness might have happened when mobile beings started moving directionally—towards food and away from dangers. For example, the tiny worm Dugesia tigrina moves based on whether it’s hungry. It uses chemoreceptors to smell its environment and guide itself to food. After eating, it retreats to safety to digest.

However, blindly following scents isn’t the same as having a direction. Adding vision was the next step toward consciousness. Vision provides depth and context to our surroundings. It was a significant leap, allowing creatures to see and pursue their goals more effectively.

But to maintain focus on a goal even when it’s out of sight, animals needed an inner representation of the world. This ability allows them to remember and stay focused on food even when it leaves their sensory range. Memory, thus, is crucial for this.

This concept, known as “object permanence,” means understanding that things continue to exist even when unseen. Some mammals, birds, and human babies develop this skill. For example, adult chickens can delay gratification, waiting for a bigger meal later rather than eating immediately. This shows a basic sense of time and future planning.

Western scrub jays exhibit even more complex behavior. They hide food for future use and rehide it if they sense another bird watching. This shows an understanding that other conscious beings exist with their perspectives. Being able to anticipate others’ actions requires a high level of consciousness and “mind-reading.”

Language takes these abilities further. Words let us create detailed plans, communicate them, and understand our own consciousness. This tool enables us to explore ideas about ourselves and our place in the universe.

So, where did our consciousness originate? It probably began with a hungry self moving toward food. This primitive urge gave it survival advantages. Over time, these small steps evolved into the sophisticated consciousness we have today. We might be building skyscrapers or dreaming of space, but at our core, much of this complexity started with the simple drive for food.