Hey there!

Today, we’re mixing things up a bit. Instead of the usual video, John Green is going to read a story from his podcast, “The Anthropocene Reviewed.” We’ll be back with regular content soon, but for now, let’s dive into this fascinating tale.

If you’ve ever been around kids or remember being one, you’ll know about hand stencils. Kids, usually between two and three, spread their fingers on a piece of paper and trace around them with help from a parent. I remember my son’s amazement when he saw the outline of his hand on the paper. It was like he’d left a semi-permanent mark of himself. Though my kids have grown up, those early hand tracings flood me with joy and remind me of how they are gradually running toward their own lives. That’s the beautiful, yet bittersweet, part of parenting: realizing they’re growing both up and away.

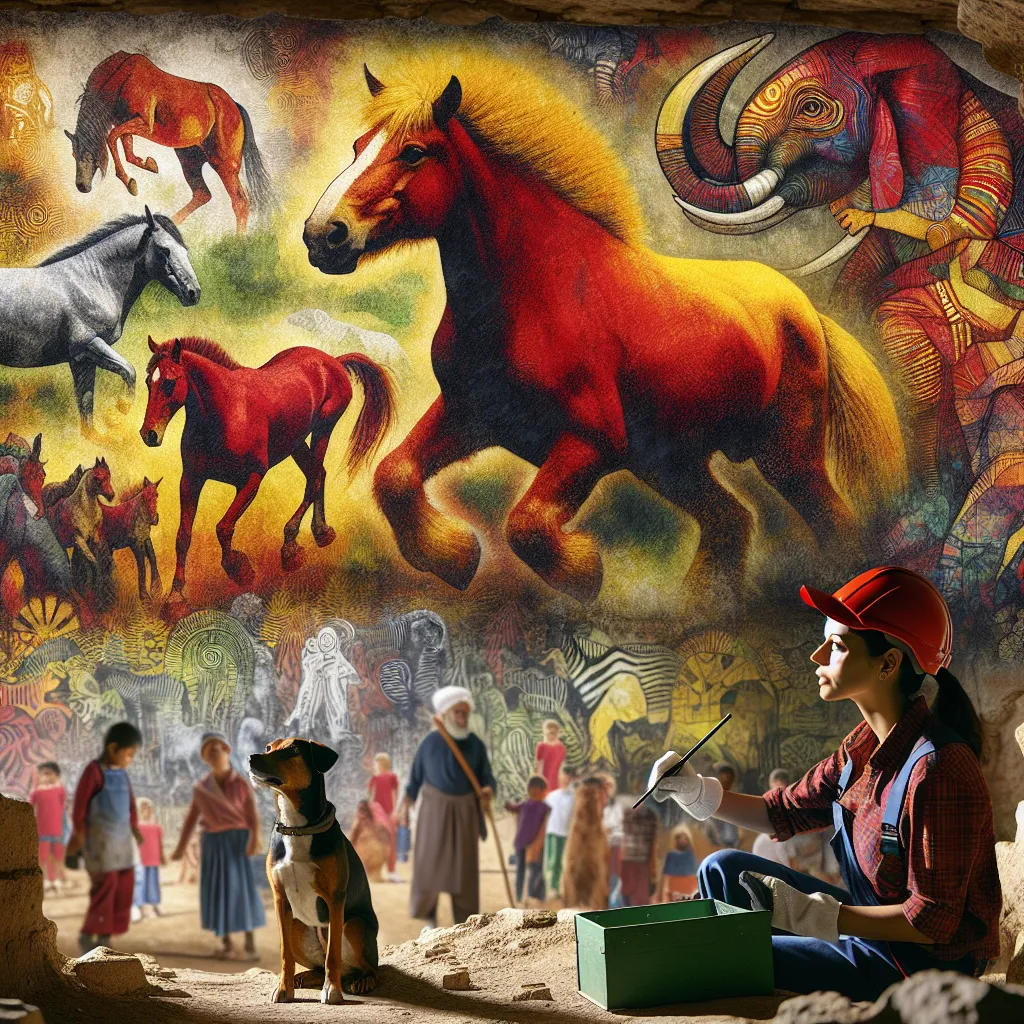

The connection between art and its viewers is like a time machine. Back in 1940, a young mechanic named Marcel Ravidat was out with his dog, Robot, in southwestern France. Robot disappeared down a hole, and when he came back, Ravidat was intrigued enough to explore the next day with some friends. What they found was astonishing: a cave with walls full of ancient paintings, over 900 images of animals like horses, bison, and even extinct species like the woolly rhinoceros. These paintings, at least 17,000 years old, were vividly detailed with red, yellow, and black pigments.

Two boys were so moved by this discovery that they camped outside the cave for over a year to protect it. After World War II, the French government took over, and in 1948, the cave opened to the public. Picasso, upon seeing these paintings, famously said, “We have invented nothing.”

However, many mysteries remain about Lascaux. For instance, why are there no paintings of reindeer, their primary food source? And why focus so much on animals rather than human forms? The cave also contains almost a thousand abstract signs and shapes that baffle us still, and a notable feature: “negative hand stencils.” These were made by pressing a hand against the wall and blowing pigment around it, leaving an imprint.

These hand stencils are found worldwide—Indonesia, Spain, Australia, the Americas, Africa—spanning thousands of years. They remind us that, despite how ancient life was tough, with high mortality rates and limited resources, our ancestors took the time to create art. Almost like art is essential to human existence. We see hands of all ages, and it’s fascinating that, despite not having contact with one another, different cultures created similar hand stencils.

The hand stencils at Lascaux, to me, say, “I was here.” They tell us, “You are not new.” There’s something ghostly and timeless about them, like hands reaching out from history itself.

Unfortunately, the real Lascaux cave is closed now due to damage caused by human breath, mold, and lichens. A replica, Lascaux II, allows people to experience the cave’s beauty without harming the original. While it may feel like an overly modern solution, it’s actually hopeful. It shows that when faced with the potential destruction of something beautiful, we sometimes choose preservation over convenience.

The discovery of Lascaux by teenagers and a dog, and the subsequent dedication to its protection, speaks volumes. When humans started posing a threat to this ancient treasure, we stopped visiting the cave. Lascaux remains, but it’s not a place we can physically go back to—it stands as a memory, much like the past it represents.

Hope you enjoyed this story, and don’t forget to check out John Green’s podcast “The Anthropocene Reviewed” for more poetic reflections on our human world.

Catch you in the next video!