In the unassuming corners of our natural world, there exists a creature so enigmatic and fascinating that it challenges our conventional understanding of intelligence and life itself. Meet the slime mold, a single-celled organism that defies the boundaries between plants and animals, and whose behaviors are as intriguing as they are intelligent.

As a child, I was captivated by these greenish-brown, slimy blobs that would mysteriously appear in our backyard. They would creep slowly across the yard, only to transform into pale pink, formless blobs that felt like dry sand stuck together. This transformation from a moving entity to an inanimate form was nothing short of magical. But what was even more astonishing was the intelligence behind these seemingly simple creatures.

Slime molds, particularly the species Physarum polycephalum, have been found to possess an intelligence that is both primitive and profound. Despite lacking a brain or nervous system, they can solve complex mazes, learn from their environment, and even recreate the efficient networks of human-made transportation systems. Imagine a creature that can navigate through a maze, avoiding dead-end corridors and finding the shortest path to its food source, all without the aid of a brain.

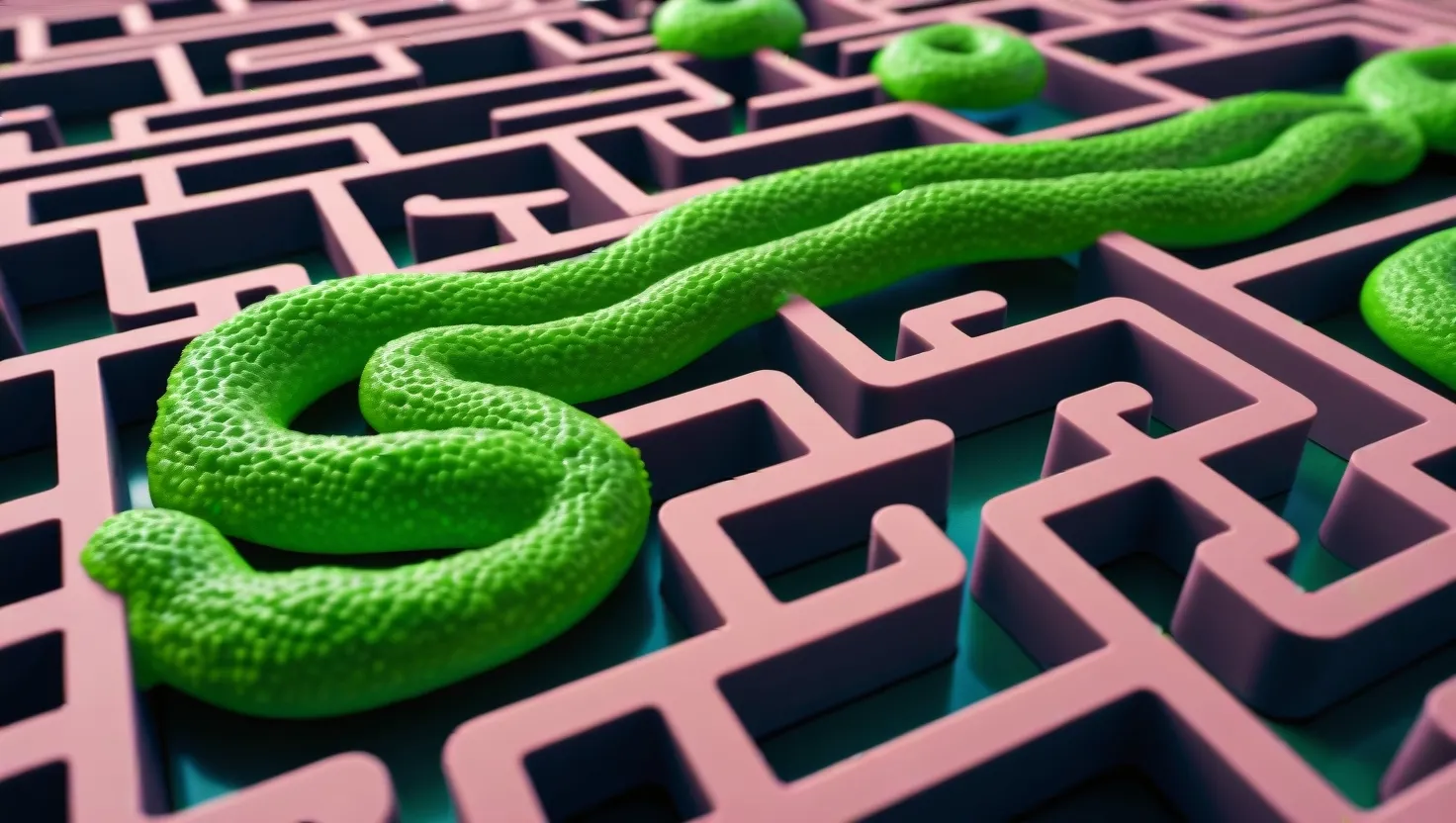

One of the most remarkable experiments involving slime molds was conducted by Toshiyuki Nakagaki and his team in Japan. They placed pieces of a slime mold in a plastic maze with blocks of agar packed with nutrients at the start and end. Within hours, the slime mold had filled the maze, but it did not do so randomly. Instead, it retracted its branches from dead-end corridors and grew exclusively along the shortest path possible between the two pieces of food. This ability to optimize routes is not just limited to mazes; slime molds have also been observed to recreate the railway networks of cities like Tokyo and the highways of the UK and Canada with startling accuracy.

But how do these brainless organisms achieve such feats? The answer lies in their unique way of processing information. Slime molds use a form of externalized spatial memory, leaving behind trails of translucent slime as they move. This slime acts as a map, helping the slime mold avoid retracing its steps and ensuring it explores new areas efficiently. This mechanism is so effective that it allows slime molds to solve spatial problems that even advanced computer simulations struggle with.

Their intelligence is not just about navigation; it also involves learning and adaptation. In an experiment where scientists coated bridges with bitter substances like caffeine or quinine, the slime mold initially avoided these areas. However, when it discovered that these substances were not harmful and that there was a reward on the other side (like oatmeal), it adapted its behavior. Over time, the slime mold learned to cross the bridges with ease, demonstrating a clear ability to learn from experience and adjust its behavior accordingly.

Slime molds also exhibit a form of mechanosensation, allowing them to detect objects at a distance without physical contact. This is achieved through proteins called TRP channels, similar to those used by human cells. These channels help the slime mold sense vibrations and tension, much like a spider senses its prey in its web. When researchers disrupted these channels, the slime mold lost its ability to detect distant objects, highlighting the crucial role these mechanisms play in its sensory capabilities.

The implications of slime mold intelligence are vast and challenging. It forces us to rethink what we consider intelligent behavior and how it is achieved. Traditional views of intelligence are often tied to the presence of a brain and nervous system, but slime molds show us that intelligence can manifest in entirely different forms. As Michael Levin from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University notes, slime molds have a “completely alien type of body” with a unique way of living and interpreting the world, yet they share with us the ability to map out their environment, make decisions, and strive for their goals.

In many ways, slime molds can be seen as nature’s organic computers, processing information in a distributed and decentralized manner. Their ability to form networks and solve complex problems collectively is a testament to the power of simple, yet coordinated, action. This collective intelligence is not just a curiosity; it has practical applications. Researchers are exploring how slime molds can inspire the design of urban transportation systems and even bio-computers modeled after the human brain.

The study of slime molds also raises questions about the evolution of intelligence. These organisms have been around for at least 600 million years, long before the emergence of brains or nervous systems. Their survival and success suggest that intelligence is not a recent innovation but a fundamental aspect of life that can manifest in various forms.

As we delve deeper into the world of slime molds, we are reminded that intelligence is not exclusive to complex organisms. It is a pervasive feature of life, found in the simplest and most unexpected places. The slime mold’s ability to navigate, learn, and adapt challenges our conventional wisdom and invites us to explore the hidden networks of natural intelligence that exist beneath our feet.

In the end, the slime mold is more than just a curious creature; it is a window into the diverse and often mysterious ways in which life expresses itself. As we continue to uncover the secrets of these peculiar life forms, we are forced to expand our understanding of what it means to be intelligent and alive. The slime mold may not have a brain, but it certainly has a mind of its own, one that is full of surprises and lessons for us all.