All around us, hidden in the microverse, there’s a brutal war raging among the true rulers of our planet: microorganisms. Amoebas, protists, bacteria, archaea, and fungi are constantly competing for resources and space. And then there are viruses, haunting the rest. Viruses, the smallest, most abundant, and deadliest beings on Earth, kill trillions daily. They aren’t interested in resources—only in taking over living organisms.

Viruses are tiny and simple, much smaller than cells or even bacteria. They’re just a hull with a bit of genetic material and a few proteins. They don’t have metabolism, propulsion, or ambition. They float around helplessly, hoping to find a host to infect. This simplicity leads to debates on whether they should be considered alive. Some scientists think they are, while others argue that the infected cells, which became viral factories, are the truly living entities.

The origin of viruses is mysterious. They need a host to multiply, so where did they come from initially? Some theories suggest they were essential in the emergence of life or maybe escaped DNA from cells that excelled at replicating. Possibly, they are descendants of lazy parasites that outsourced their work. Current thought is that viruses likely emerged multiple times from different origins, but it’s still unclear. What’s certain is their success: there are an estimated 10,000 billion billion billion viruses on Earth. Lining them up would stretch 100 million light-years, across 500 Milky Way galaxies.

Recently, scientists discovered something even stranger: giant viruses, or “gyruses.” These break records and challenge our understanding of viruses. Gyruses even come with their own parasites, called virophages, viruses that hunt other viruses. Since the first one was identified in 2003, these gigantic viruses have been found everywhere—oceans, water towers, pig guts, and human mouths.

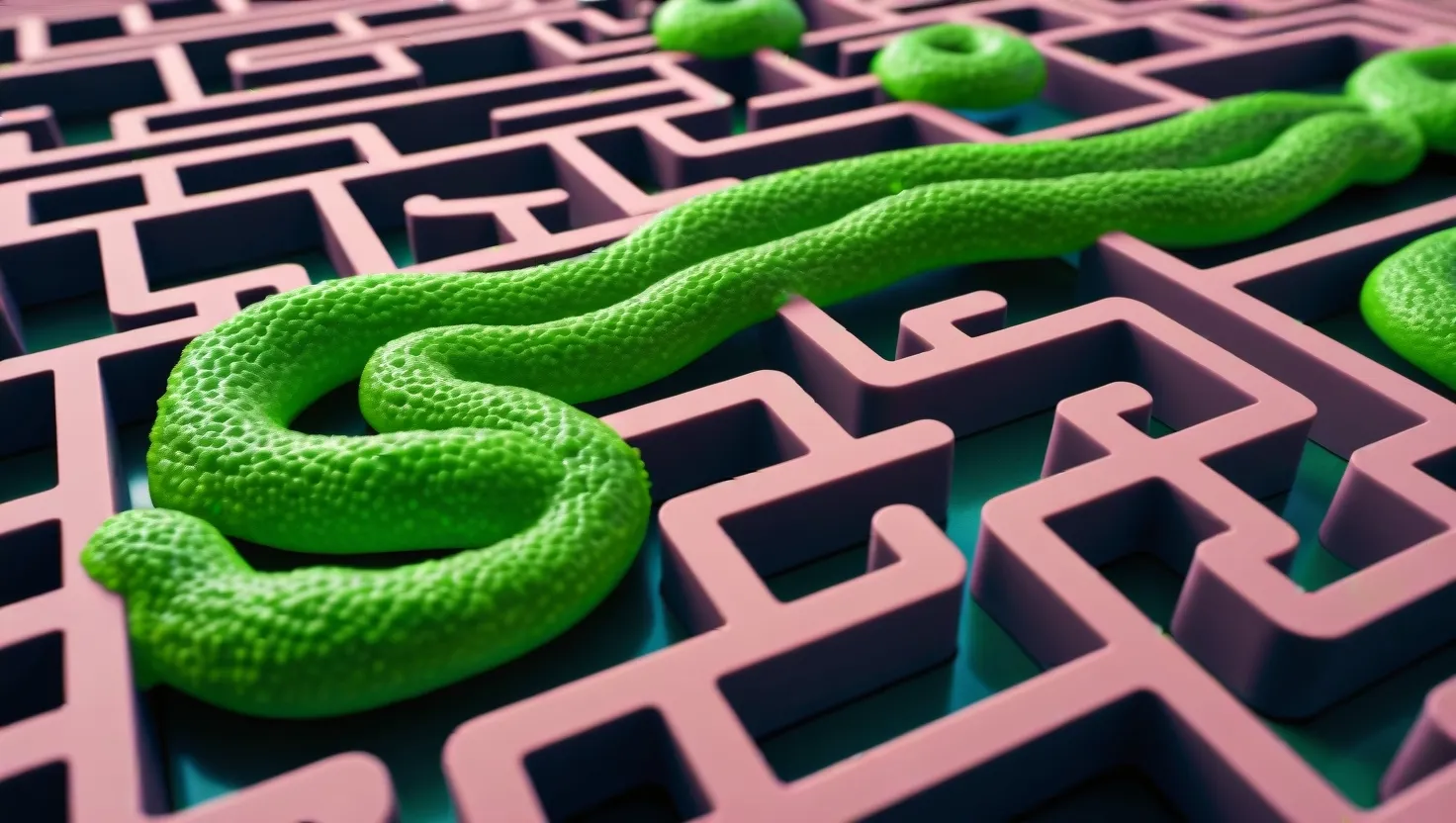

Gyruses are visually bizarre: hairy geometric forms or mini pickles, much larger than any virus known before. They were mistaken for bacteria under microscopes for centuries. Imagine discovering elephant-sized ducks in your backyard all of a sudden! These massive viruses mostly hunt amoebae and other single-celled organisms. When they find a victim, they take over its cellular machinery to reproduce, using the host’s resources to build more gyruses, eventually causing the cell to self-destruct.

What really makes gyruses unique isn’t their size but their complexity. Unlike most viruses with a handful of genes, gyruses can have hundreds or even thousands. This blurs the line between living and non-living. Some of their genes are so complex that they might regulate nutrient intake, energy production, and replication—tasks we associate with living organisms. There’s even speculation that some gyruses might maintain a basic level of metabolism, shaking our understanding of what a virus really is.

Gyruses might fundamentally alter their hosts’ evolution, possibly integrating their DNA with the host’s. Over billions of years, they could have shaped life by mixing genes in new ways, not just as parasites but as major influencers in the evolutionary process.

Adding another layer of complexity, virophages hunt gyruses. This concept is mind-boggling: can something possibly dead hunt another thing that’s also possibly dead? Take Sputnik, a virophage hunting the Mama virus, which in turn hunts amoebae. Sputnik hijacks the Mama virus’s reproduction within the amoeba, drastically reducing its efficiency while producing more virophages instead.

Gyruses aren’t defenseless. Similar to bacteria’s CRISPR defense system, some have their own immune-like defenses against virophages. Some protists even incorporate virophage DNA into their own genomes to fend off gyruses, sacrificing themselves but preventing further infection of their kind.

Despite all we’ve discovered, we’re still at the beginning. It’s been less than 20 years since we found gyruses and virophages, and there’s so much we don’t know about the microverse. Life and its complexities are like a sprawling, fascinating game happening on an unfathomable microscopic scale. Whenever you think there’s nothing new to discover, remember the hidden world of giant viruses and the mysteries they reveal.