The Voynich Manuscript, a 15th-century codex, is a puzzle that has captivated the imagination of scholars and the general public alike for centuries. This mysterious book, with its 240 pages of cryptic symbols, intricate diagrams, and bizarre illustrations, has become a legendary challenge in the realms of cryptography, linguistics, and historical research.

As I delve into the world of the Voynich Manuscript, I am reminded of the words of the renowned cryptographer, William Friedman: “No one has yet been able to decipher the text, and it is possible that it will never be deciphered.” This statement, though made decades ago, still resonates today, highlighting the manuscript’s enduring enigma.

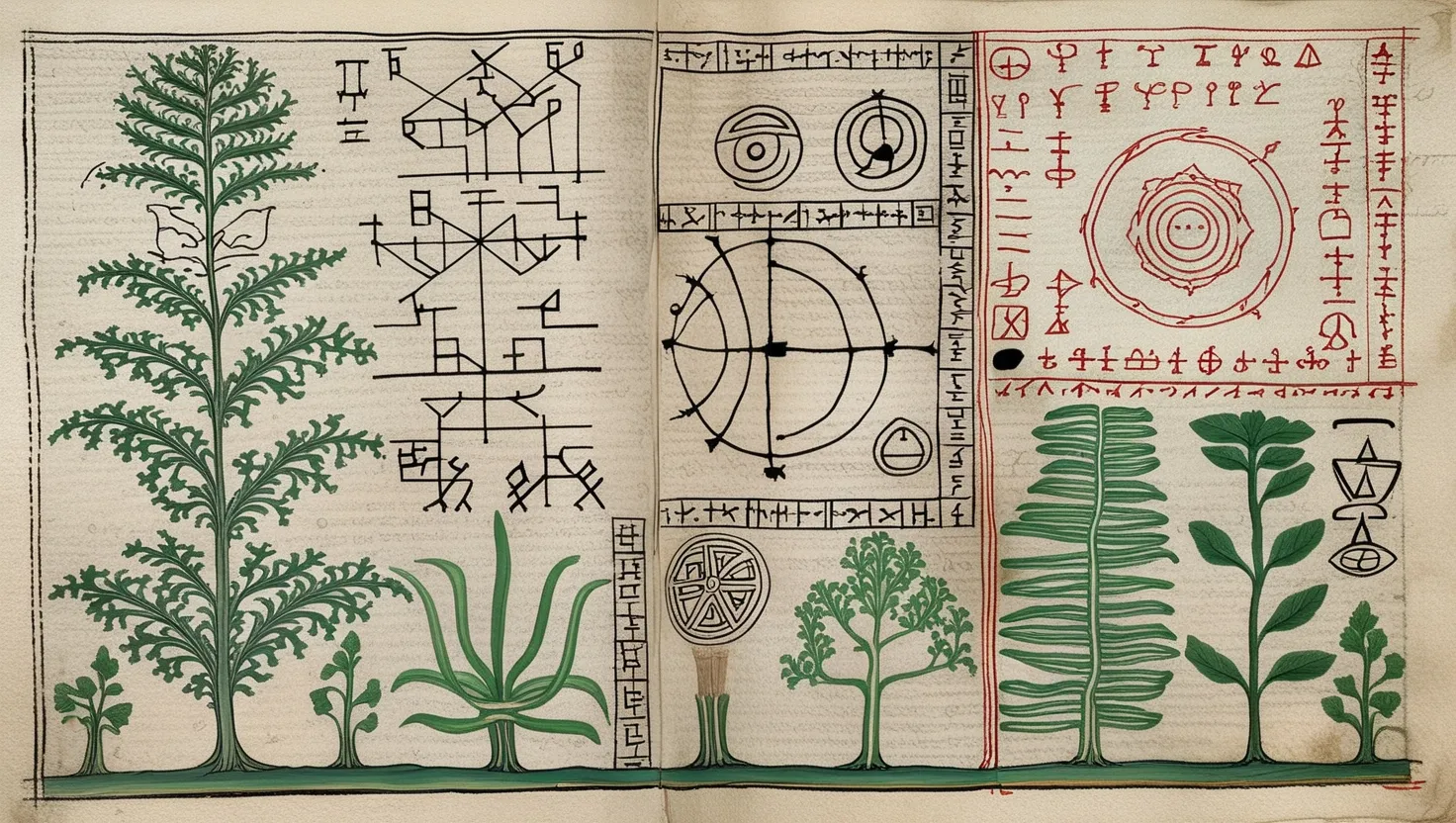

The manuscript’s content is as fascinating as it is perplexing. It includes drawings of plants that do not match any known species, astronomical charts that defy modern understanding, and nude female figures engaging in activities that are both mystifying and intriguing. The text itself, comprising over 170,000 characters, seems to follow linguistic patterns but remains stubbornly indecipherable.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Voynich Manuscript is its history. Discovered in the early 20th century by Polish book dealer Wilfrid Voynich, the manuscript has a documented history that dates back to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who purchased it for a substantial sum of 600 gold ducats in the late 16th century. However, the 150 years preceding this purchase remain shrouded in mystery.

Recent research by Stefan Guzy has shed some light on this period. By analyzing imperial account journals, Guzy has identified a possible earlier owner of the manuscript: Carl Widemann, a physician who sold a collection of rare books to Emperor Rudolf II. This discovery, though not definitive, adds another layer to the manuscript’s complex history.

Theories about the manuscript’s origin and purpose are as varied as they are intriguing. Some believe it to be an elaborate hoax, perhaps created by a medieval prankster or even a modern forger. However, the carbon dating of the parchment and the ink, which places its creation between 1404 and 1438, strongly suggests that it is a genuine medieval artifact.

This period, marked by significant advancements in science and alchemy, has led many to speculate about the manuscript’s connection to early scientific experimentation or esoteric knowledge. The illustrations of plants and astronomical diagrams suggest a deep understanding of natural sciences, while the text’s resistance to decryption hints at a sophisticated coding system.

The use of artificial intelligence in recent years has opened new avenues for deciphering the Voynich Manuscript. By leveraging advanced AI techniques such as transformer models and transfer learning, researchers are attempting to find patterns and connections that have eluded human analysts for centuries. This approach, though still in its infancy, holds promise in potentially uncovering the secrets hidden within the manuscript’s text.

As I ponder the Voynich Manuscript, I am drawn to the idea that it might be written in a constructed language or an unknown form of steganography. The concept of a constructed language, or “conlang,” is not new; historical examples like Balaibalan, a language based on Turkish, Persian, and Arabic, show that such languages have existed in the past.

The manuscript’s illustrations, particularly the nude female figures in tubular structures, have sparked a range of interpretations. Some see these as representations of alchemical processes, while others view them as part of a mystical or spiritual text. The absence of any clear context makes these interpretations as speculative as they are fascinating.

The Voynich Manuscript also raises questions about the limits of human knowledge and our ability to understand historical artifacts. As technology advances, our tools for analysis become more sophisticated, but the manuscript remains a constant challenge. It forces us to consider the possibility that some secrets may be lost forever, hidden behind a veil of cryptic symbols and illustrations.

In the words of the cryptographer James Gillogly, “The Voynich Manuscript is like a Rosetta Stone, but without the parallel text to help decipher it.” This analogy highlights the manuscript’s unique position as a key to understanding a lost language or coding system, but one that remains locked due to the absence of a clear key.

As we continue to grapple with the Voynich Manuscript, we are reminded of the complexity and richness of human history. This mysterious codex is more than just a puzzle; it is a window into a past that is both familiar and alien, a testament to the ingenuity and creativity of our ancestors.

The Voynich Manuscript’s enduring mystery is a call to action, a challenge to scholars and researchers to continue exploring new methods and perspectives. Whether it is an indecipherable code or an elaborate hoax, the manuscript remains an intriguing enigma that continues to captivate our imagination and inspire our curiosity.

In the end, the Voynich Manuscript stands as a reminder that some mysteries may never be fully solved, but it is in the pursuit of these mysteries that we find true intellectual and creative fulfillment. As the famous cryptographer, Claude Shannon, once said, “The enemy knows the system very well. He must be presumed to be a genius.” In the case of the Voynich Manuscript, the “enemy” is the unknown author, and the “system” is the intricate web of symbols and illustrations that continue to baffle us. The pursuit of deciphering this system is a journey that is as rewarding as it is challenging.